Through a Stakeholder Analysis and Training Needs Assessment (TNA), our team collected stakeholder responses to better understand internal training needs and external challenges for the enhancement of Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Green Care sector.

The Green4C project, co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union, has an overarching and ambitious aim of integrating business and scientific sectors that are currently disconnected: the health and social inclusion sectors and the nature-based sectors in both rural and urban areas. This project aims to organise diverse activities such as an online training course, a business innovation challenge, a specialisation school and Green4C hackathons. Understanding the training needs of different stakeholders and the challenges that the initiatives in this sector face, represents the first stepping stone.

The “Green4C stakeholder analysis and Training Needs Assessment (TNA)” report (download the full document here) is a first attempt at portraying the complex picture of social innovation and entrepreneurship activities, and of relevant training opportunities currently available in the Green Care sector more generally.

The main data collection methods for this analysis included academic and grey literature review, a TNA questionnaire and in-depth interviews: a total of 206 responses from 49 countries for the TNA were received and 16 in-depth interviews with experts and practitioners from 10 countries were carried out. As a result of the analysis, a list of beneficiary categories of the Green4C project was defined. The major conclusions of the analysis presented in the report are summarised here.

What specific skills and knowledge are needed in Green Care?

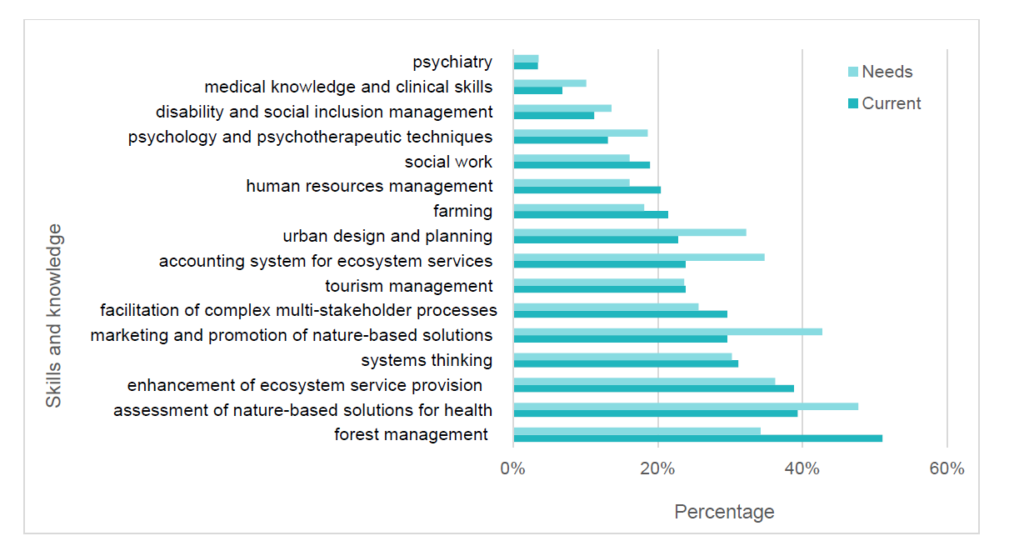

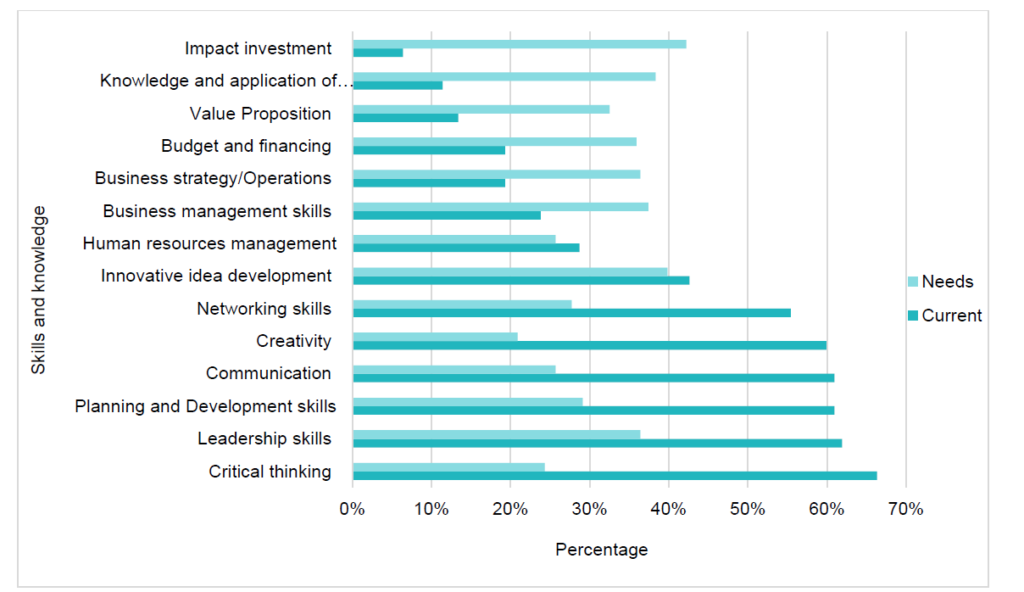

When comparing current and future involvement in the Green4C thematic sectors, responses show a clear trend of growing interest in the sector as well as a specific need for business training to be applied in the fields of Green Care and nature-based solutions to health, wellbeing and social inclusion. Respondents would like to acquire skills and knowledge mostly in: impact investment, innovative idea development, knowledge and application of cutting-edge technology, business management skills, business strategy/operations, value proposition, budget and financing (Figure 1 and 2).

What are the main take-home messages?

Legal and regulatory framework for entrepreneurship and innovation in Green4C thematic sectors:

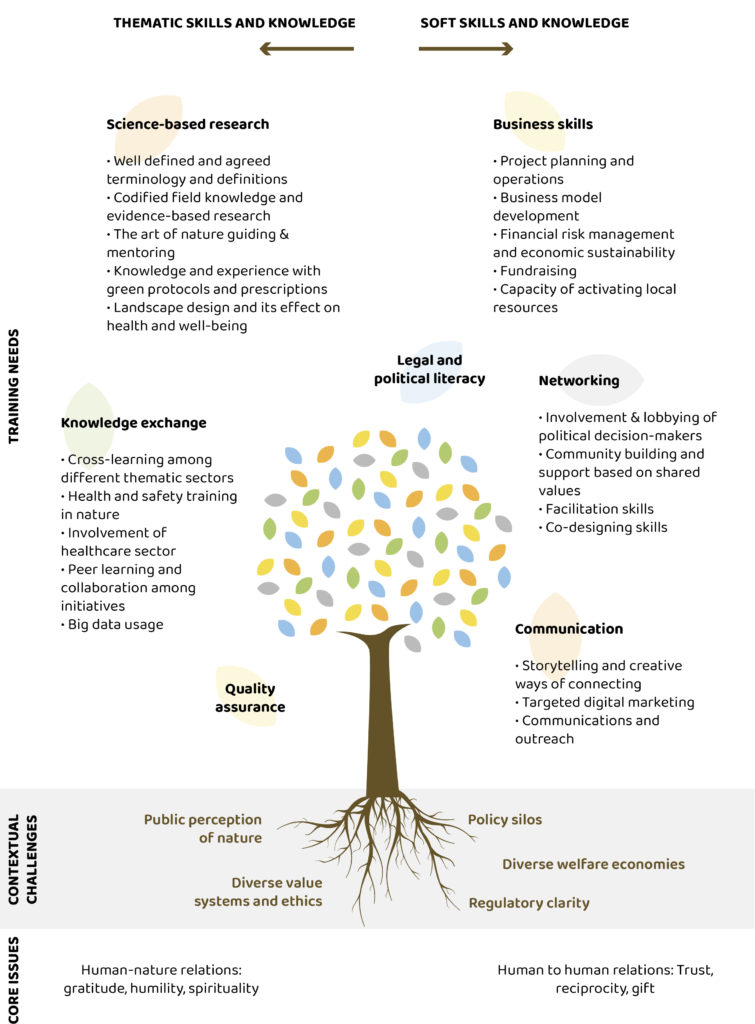

At present, differences among sectors, national and local laws and regulations provide uneven access to training and opportunities for business development in the sector. Green4C activities and trainings can help to improve legal and political literacy among new and emerging entrepreneurs who need to navigate through complex regulatory systems to establish and advance their businesses in the Green Care sector.

Facilitating knowledge exchange, learning and co-designing:

Acknowledging that facilitation is an important element for developing Green Care activities, investing in exchange, learning and co-designing processes will help define the success of initiatives in this sector. Thus, Green4C training courses and follow-up activities can focus on improving knowledge, skills and competences of participants in facilitation.

Enhancing public-private involvement across sectors:

There is a need to involve the public sector, and more specifically the health sector, in the development of new social entrepreneurship activities. While in some thematic sectors, private business models are more developed and market access is well established, in others, services continue to be provided mainly by the public sector and require public sector involvement: there is thus a need for greater knowledge sharing and skill building for business models to be developed through public-private partnerships.

Peer-learning and knowledge sharing:

Peer-learning and knowledge sharing is needed for stakeholders from diverse countries and involved in diverse thematic sectors. While thematic sectors are more developed and thus regulated in some countries rather than others, also available training opportunities in Green4C thematic sectors differ across countries.

Focussing on co-designing and co-creation through case-studies and best practices:

Training should focus on co-designing and co-creation skills as a way to ensure that the services offered respond to needs specifically connected to demands from the market.

Professional sector-specific mentoring:

Business support is needed in all the areas, including: idea development, development of the business model, trend analysis, product development and/or co-designing, business plan, communication and marketing as well as networking.

“For” or “not-for” profit business models:

Business development in Green Care is often undertaken by a cooperative or social enterprise/association, or in the case of a for-profit business, entails close collaboration with public or private stakeholders in the co-creation of the final service or product. Thus, social innovation is often found in new networks, partnerships, relationships, attitudes and governance arrangements. This means that training will be focusing on social innovation and entrepreneurship, as well as design elements and teaching tools such as the social business Canvas model. Connections to a variety of good practices and networks in this field will also be key.

Investment in research and development:

Training opportunities should include access to cutting-edge research to provide trainees and new businesses with science-based information to develop their social entrepreneurship and business models, properly communicate and market the designed services and activities, and finally, apply monitoring tools to the practice.

Identification and development of tools and further context analysis:

Training opportunities need to be based on providing tools for improving the quality of the services developed.

Some of the training needs mentioned above could be addressed through the training courses and capacity building offered within this project. Green4C offers the opportunity to develop new and innovative training for emerging and future Green Care professionals. The project aims to complement a rich and varied offer in training already available from the university to the professional level integrating a set of four different thematic sectors through the development of new business models. As an Erasmus+ project, Green4C can also address some of the external challenges the sectors face: by enhancing visibility of these sectors, by engaging in political discussions about the promotion of nature-based solutions and Green Care approaches, and and by creating the basis for stakeholder alliances, thematic communities as well as peer and cross-sectoral learning.

Find out more by reading the whole report here!

References

- Ackermann, F., Eden, C., 2011. Making strategy: Mapping out strategic success. Sage.

- Andersen, E.S. (2008), Rethinking Project Management: An Organisational Perspective, Prentice-Hall/Financial Times, Harlow.

- Arts, B., Goverde, H. (2006). The governance capacity of (new) policy arrangements: a reflexive approach. In: Arts, B., Leroy ds.), Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance. Environment and Policy, 47:69–92.

- Babou, I., Callot, Ph. (2009). Slow tourism, slow (r)évolution? Cahier Espaces, 100, 48–54.

- Casson, M.C., Della Giusta, M., Kambhampati, U.S. (2010). Formal and informal institutions and development. World Development, 38(2), pp.137-141.

- Clarke, N. (2003). The politics of training needs analysis. Journal of Workplace Learning, 15(4), 141-153. doi: 10.1108/13665620310474598

- Cromer, C.T., Dibrell, C., Craig, J B. (2011). A study of Schumpterian (radical) vs. Kirznerian (incremental) innovations in knowledge intensive industries. Journal of strategic innovation and sustainability, 7(1), 28-41.

- Darcy, S., Dickson, T. (2009). A Whole-of-Life Approach to Tourism: The Case for Accessible Tourism Experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 16(1), 32-44.

- Di Iacovo, F. and O’Connor, D., 2009. Supporting Policies for Social Farming in Europe. Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas. SoFar project: supporting EU agricultural policies. Arsia, Florenz (Italien).

- Drucker, P. (2014). Innovation and entrepreneurship. Routledge.

- Eskerod, P., Huemann, M. (2013). Sustainable development and project stakeholder management: What standards say. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business.

- Fonte, M., Cucco, I. (2017). Cooperatives and alternative food networks in Italy. The long road towards a social economy in agriculture. Journal of rural studies, 53, 291-302.

- Freeman, R.E. (1984), Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, Pitman/Ballinger,Boston, MA.

- Gould, D., Kelly, D., White, I., Chidgey, J. (2004). Training needs analysis. A literature review and reappraisal. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(5): 471-86

- Guion, L.A., Diehl, D.C. and McDonald, D., 2011. Triangulation: Establishing the validity of qualitative studies. University of Florida IFAS Extension. Online Document.

- Hagedoorn, J. (1996). Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Schumpeter Revisited. Industrial and Corporate

- Hansen, M. M., Jones, R., Tocchini, K. (2017). Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy: A state-of-the-art review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(8), 851.

- Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., … Schnabel, P. (2011). How should we define health?. Bmj, 343.

- Hunter, M. R., Gillespie, B. W., Chen, S. Y. P. (2019). Urban nature experiences reduce stress in the context of daily life based on salivary biomarkers. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 722.

- IUCN (2013). Nature-based solutions. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature Available at: https://www.iucn.org/commissions/commission-ecosystem-management/our-work/nature-based-solutions

- Kondo, M. C., Jacoby, S. F., South, E. C. (2018). Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments. Health & place, 51, 136-150.

- Loch, C. and Kavadias, S. (2011), “Implementing strategy through projects”, in Morris, P.W.G., Pinto, J.K., So¨derlund, J. (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Project Management, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). (2005). Overview of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Available at: http://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/About.aspx#1

- OECD. (2010). Social Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation. SMEs, Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/14506/attachments/22/translations/en/renditions/native

- Palinkas, L.A., Horwitz, S.M., Green, C.A., Wisdom, J.P., Duan, N. and Hoagwood, K., 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and policy in mental health and mental health services research, 42(5), pp.533-544.

- Pawlyn, J., Carnaby, S. (2009). Profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: nursing complex needs. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Poulsen, M. N. (2017). Cultivating citizenship, equity, and social inclusion? Putting civic agriculture into practice through urban farming. Agriculture and Human Values, 34(1), 135-148.

- Rook, G. A. (2013). Regulation of the immune system by biodiversity from the natural environment: an ecosystem service essential to health. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(46), 18360-18367.

- Secco, L., Pisani, E. , Da Re, R. , Vicentini, K. , Rogelja, T. , Burlando, C. , Ludvig, A. , Weiss, G. , Zivojinovic, I., Górriz-Mifsud, E., Marini-Govigli, V., Martínez de Arano, I., Melnykovych, M., Tuomasiukka, D.,, Den Herder, M., Lovric, M., Ravazzoli, E., Dalla Torre, C., Streifeneder, T., Vassilopoulos, A., Akinsete, E., Koundouri, P., Lopolito, A., Prosperi, M., Baselice, A., Polman, N., Dijkshoorn, M., Nijnik, M., Miller, M., Barlagne, C., Hewitt, R., Prokofieva, I., KuvlankovaOravska, T., Špaček, M., Brnkalakova, S., Gezik, V. (2019). Manual on Innovative Methods to Assess SI and its Impacts. Deliverable 4.3, Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA), pp: 1-203.

- Sempik, J., Hine, R. Wilcox, D. eds. (2010) Green Care: A Conceptual Framework, A Report of the Working Group on the Health Benefits of Green Care, COST Action 866, Green Care in Agriculture, Loughborough: Centre for Child and Family Research, Loughborough University.

- SHIN, Won Sop. (2015). Forest Policy and Forest Healing in the Republic of Korea. International Society of Nature and Forest Medicine. Available at: https://www.infom.org/news/2015/10/10.html

- van den Bosch, M., Sang, Å. O. (2017). Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health–A systematic review of reviews. Environmental research, 158, 373-384.

- WHO (1948). Constitution for the World Health Organization. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- World Bank. (2013). Inclusion Matters : The Foundation for Shared Prosperity. New Frontiers of Social Policy;. Washington, DC. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16195 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.